William Henry Seward was U.S. secretary of state from 1861 to 1869, after serving as governor and senator of New York. As secretary of state for Presidents Abraham Lincoln and Andrew Johnson, he coordinated the purchase of the territory of Alaska from Russia for $7.2 million.

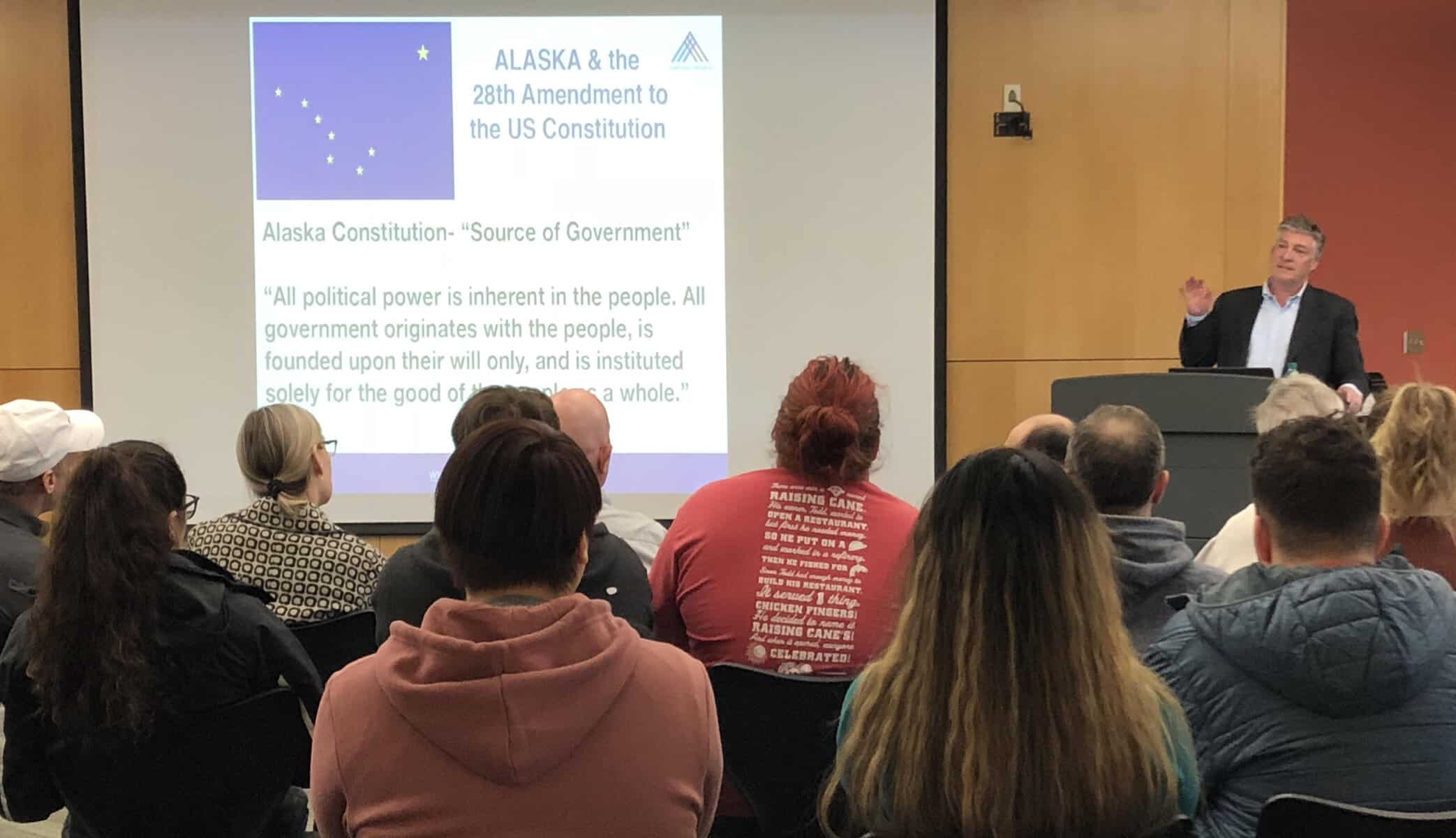

American Promise President Jeff Clements spoke about Seward’s leadership and legacy at the University of Alaska-Anchorage during his trip to Alaska earlier this year: “William Henry Seward is at the top of a short list of our greatest secretaries of state. He kept the European powers from recognizing the Confederacy and kept them out of the conflict. Side by side with President Lincoln he helped win the Civil War and free the slaves. And of course, he is responsible for Alaska becoming part of the United States of America.”

Below are excerpts from Jeff’s talk about Seward’s work and how it inspires and connects with American Promise and its movement to get big money out of politics through the 28th Amendment.

It is reasonable today to be uneasy, to say the least, about the Alaska territory purchase—a massive real estate transaction between two continental powers with no consultation whatsoever with those who lived in the land. That tension between our founding principles and our actions as a nation is a through-line in American history: a nation founded on the principle that all men are created equal; a nation that destroyed native nations and enslaved millions of its people. How can we possibly reconcile these things?

This is the question of our time, as it was the question of William Henry Seward’s time. If we remain dedicated today to the principle that all humans are equal before our law, then every serious departure from that principle is indeed an “irrepressible conflict,” as Seward described the question of slavery and freedom.

Seward was a man of his time, but he had an uncommon dedication to the principle of political equality and the equal rights of all, even as he was a crafty and shrewd politician and diplomat. Like Lincoln, Seward was a very good lawyer, and as a lawyer myself, I was particularly struck in reading recently about his defense of two African Americans in two trials in the summer of 1846.

Each defendant, Henry Wyatt and William Freeman, had only recently left prison in upstate New York, where Seward lived, and the facts of the crimes were particularly gruesome and horrific. People living in Seward’s town of Auburn, New York, and the nearby region were inflamed with outrage and a spirit of revenge, and no one but Seward would represent the prisoners.

Think of it: Seward had recently been governor of New York and returned to his law practice more or less broke from the years of minimal pay in the governor’s office. He had future political ambitions and wanted to make a living in his law practice in the meantime. Yet he took on two of the most unpopular clients you can imagine, giving their defense everything he had, with no pay.

His family and friends urged him to abandon the men, but he refused to do so. Seward’s closing argument to the all-white jury was a passionate appeal to the sense of equality that must be the guide to justice: “The color of the prisoner’s skin, and the form of his features are not impressed upon the spiritual, immortal mind which works beneath. He is still your brother and mine, and bears equally with us the proudest inheritance of our race—the image of our maker. Hold him then to be a man. Exact of him all the responsibilities which should be exacted under like circumstances if he belonged to [your] race, and make for him all the allowances, which, under the circumstances, you would expect for yourselves.”

When the defendants nonetheless were convicted, Seward returned to his law practice, as he said, “exhausted in mind and body, covered with public reproach, and stunned with duns and protests.” Can you imagine a politician today having the courage to take on such a defense to get nothing in return but the scorn and anger of his neighbors and friends, not to mention his enemies?

And yet Seward did take that on.

He went on to help launch the Republican Party, committed to ending slavery; served with remarkable distinction in the Senate; gracefully conceded to Abraham Lincoln when he lost what had been a near-certain nomination to be the Republican candidate for president; and served at Lincoln’s side as secretary of state, indispensable to the cause.

That cause was the same cause of political equality—the founding principle of the nation—that had led him 20 years earlier to take on the defense of Henry Wyatt and William Freeman.

Equal Rights of Every American

At American Promise, we are bringing all Americans together who share our belief in this fundamental principle of American self-government—the equal rights and responsibilities of every American—and are working to secure it in the future of our republic with the next amendment to the U.S. Constitution.

Earlier this year we worked with Congressmen Ted Deutch, a Democrat from Florida, and John Katko, a Republican from the part of upstate New York Seward called home, to introduce a proposal in the U.S. House for what will be the next amendment to the U.S. Constitution. The Democracy for All Amendment is expected to soon be introduced in the U.S. Senate. Its few simple words have profound meaning and impact:

“To advance democratic self-government and political equality, and to protect the integrity of government and the electoral process, Congress and the States may regulate and set reasonable limits on the raising and spending of money by candidates and others to influence elections [and] may distinguish between natural persons and corporations or other artificial entities created by law.”

The introduction of the amendment is an important step in the call for change in our political system, so our elected officials listen to We the People rather than wealthy individuals, corporations, unions and special interest groups. The work of American Promise focuses on three key questions:

- Why do we need a Constitutional amendment now?

- How does Constitutional change happen in America?

- What is our strategy for winning and how can all of us help?

Why a Constitutional Amendment?

We recognize, as did James Madison long ago, that we should amend the U.S. Constitution only on “great and extraordinary occasions.” We believe the nation now faces such an occasion.

American democracy is in trouble. The most recent global Democracy Index is sobering:

- More than a third of the globe—billions of people—now live under full authoritarian regimes.

- Less than 5% of people worldwide live in what the index defines as a successful democracy.

- Several former successful democracies have been downgraded to “flawed.” These include Taiwan, Chile and the United States.

Urgent problems in the United States are neglected due to politicians’ inability to make the necessary decisions to ensure a dynamic economy, take action against the looming climate catastrophe, tackle $22 trillion in national debt, and counter a deadly opioid crisis, while deep, dangerous anger and division worsen across the country.

We keep trying to elect just the right person, find just the right legislation that somehow can provide a way out of this dysfunction. But what if the problem is deeper than politics, elections or legislation?

What if, as American Promise adviser and former Iowa Congressman Jim Leach says, the U.S. Supreme Court has “genetically modified our national democratic DNA, pushing us toward corporatism and oligarchy”?

He refers to the recent wave of Supreme Court decisions that have struck down state and federal election and voting rights laws on the theory that unlimited money—whatever the source—in elections and lawmaking is simply free speech.

Before our time, federal and state laws regulated how money could be used in elections. Not until 1976 did the Supreme Court apply the First Amendment to any federal or state election contribution or spending limit, and not until 2010 did the Supreme Court rule that corporations or unions have a free speech right to spend their money for or against candidates to influence the outcome of elections.

Why are so many Americans so troubled by the Supreme Court’s current direction? They recognize not just that the decisions are wrongly decided but that the reasons for the error go to the heart of the same question of political equality that has run through our history, and will decide whether American democracy can survive our third century.

Basing representation and power on concentrated wealth is exactly the kind of system the British government had in 1776 and that the American Revolution rejected, and the same system the Russian government on the other side of Seward’s negotiating table had. It’s called aristocracy or plutocracy, and it’s been common in human affairs then and now.

Democracy and republican self-government are uncommon and rare, and if we want to keep this system, we need to act fast.

That’s why we need the 28th Amendment: to restore and guarantee political equality and anti-corruption principles in the First Amendment and the Constitution.

How Constitutional Change Happens in America

In the law, we apply the doctrines and the landmark decisions of the Supreme Court. But we largely ignore the much bigger landmark shifts that the American people —not the courts—lead to define and defend our Constitutional democracy.

But the story of American democracy is the story of Constitutional amendments, including the Bill of Rights, a ban on slavery, and a right to vote for all citizens regardless of race, gender or age over 18. These are huge, permanent reforms, and none happened without Americans believing in and using the Constitutional amendment process.

Here’s something else about our history: Americans don’t turn to the amendment process when things are working fine; we do it when everything’s falling apart.

Every successful reform era has included Constitutional amendments. As history teaches us, if we think we’re in a time of disruption and peril for democracy, we’d better figure out how to win Constitutional amendments again.

How We Will Succeed

We launched American Promise in January 2016 with a strategy to ratify the amendment by July 4, 2026. Now we are empowering Americans to win the 28th Amendment through a cross-partisan, citizen-powered national movement working to gain approval by ⅔ of Congress and ratification in 38 states.

So far 19 states and 800 cities and towns across the nation have passed resolutions calling for this 28th Amendment, usually by yes votes of over 75%.

Thanks to the work of our members, 250 candidates across the political spectrum last year agreed to the American Promise Pledge and support of this amendment, and more than 280 members of Congress have committed to voting for it.

American Promise is leveraging the consensus that Americans feel across partisan lines about big money in politics and working in the tradition of William Henry Seward and the generations of Americans who fought for the 27 amendments that protect our equal rights and our responsibility to preserve a government of the people, by the people, for the people.