For the majority of today’s Americans, many of the fundamental rights we hold most dear—the right to freedom, liberty, to vote, to political participation—were not granted in the original text of the Constitution. Every generation of Americans, however, has organized and stood up to demand revisions to our founding documents to expand these fundamental rights. No person exemplified this spirit of fundamental change through movement-building more than Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

Martin Luther King Jr. Day, January 20, is a day to reflect upon the legacy of the great civil rights leader. As a leader of the 1960s Civil Rights Movement, King was instrumental in the success of transformational reforms, including the 24th Amendment abolishing the poll tax, which had been used to disenfranchise poor and minority communities.

Another key Civil Rights-era achievement was the Voting Rights Act. The law expanded voting protections and specifically prohibited tactics, such as literacy tests, which disproportionately blocked African Americans from voting. It also required states with a history of discrimination to get federal approval for any changes to voting laws. That portion of the law, however, was struck down in 2013 by the Supreme Court in Shelby County v. Holder. In the years following, several states previously subject to such review have shut down polling places in areas with large minority populations.

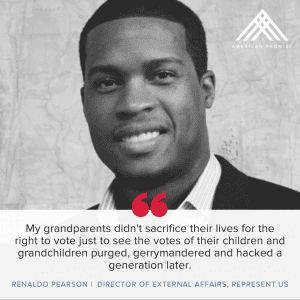

The Shelby decision was a primary source of motivation for activist Renaldo Pearson’s nearly 700-mile Democracy911 walk from Atlanta to Washington, D.C. He started his walk at King’s final resting place on August 6, 2019, the 54th anniversary of the passage of the Voting Rights Act. The demonstration culminated on the steps of the U.S. Capitol Building, with protesters calling for an end to political corruption and a restoration of voting rights protections.

The Democracy911 platform included demands that “all presidential candidates pledge to address comprehensive democracy reform in the first 100 days of their administration” so that the U.S. Senate passes legislation implementing three reforms: protect our right to vote, make elections secure and competitive, and end political corruption.

Pearson, director of external affairs at RepresentUs, says the myriad threats to democracy can’t be addressed until we fix the most fundamental one: big money in politics. The unbridled flow of money into the political system affects voters on both sides of the aisle, ushering in corruption, gerrymandering and lack of transparency. As part of the growing grassroots movement for the 28th Amendment to get big money out of politics, citizen leaders like Pearson—a D.C. native and alumni of Morehouse College, the alma mater of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.—are rising up to carry forth the torch of civic activism and reform.

In this Q&A, Pearson shares his insights on activism and the importance of the Democracy911 walk.

Why do you care about the issue of political corruption? Why do you feel it’s so critical to address this issue at this time considering all the issues our nation faces?

Why do you care about the issue of political corruption? Why do you feel it’s so critical to address this issue at this time considering all the issues our nation faces?

Renaldo Pearson: I care about the issue of political corruption because it’s the single most intersectional issue of our time. Across the gamut of public interest, wherever there is obstruction preventing a highly supported policy or solution from addressing a major problem facing the public, corruption is the culprit—be it voter suppression, partisan gerrymandering, or the corrupting influence of big money in politics. Even now, as we face unprecedented existential emergencies—like the new normal of more mass shootings than days in a year, or the new deadline of less than 11 years before it’s game over on global warming—it’s corruption that prevents us from even addressing these life-threatening phenomena.

Why did you choose to walk as a form of civic activism?

RP: Gandhi walked; Rosa Parks sat, and the black Montgomery community responded by walking instead of taking the bus; Otis Moss Sr. walked; James Meredith walked; and so did Granny D Haddock (all long distances). I thought it was important to declare a state of emergency on our broken and corrupt democracy, but I’m only one man. So, to have maximum impact, I thought it was important to use this form of escalating nonviolent direct action to continuously sound the alarm over seven weeks so that this message could have the greatest chance of sticking and reverberating—while also taking solace in symbolically tracing the footsteps of these great forebears.

You started on the anniversary of the Voting Rights Act and in the final resting place of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. What historical context did you see for this walk and how is that context relevant today?

RP: I thought it was important to start on the anniversary of the 1965 Voting Rights Act (at the King Memorial Tomb) because not enough attention has been paid to the fact that the Supreme Court gutted the VRA in 2013 [Shelby County v. Holder], making our generation the first to witness America become LESS democratic. In the wake of this decision, we’ve seen hundreds of polling places close en masse, and unprecedented millions purged from the rolls. I thought it was important to send a message to news pundits and presidential candidates that when they continue to debate about 2016 and 2020 outcomes without mentioning these actions, they do so at the risk of dismissing—if not disrespecting—the blood-drenched sacrifice of the Civil Rights Movement. My grandparents did not sacrifice their lives for the right to vote just to see the votes of their children and grandchildren purged (or gerrymandered and hacked) a generation later.